Urban Campus 1890-1938

When Northeastern was founded in 1898, the school offered classes in the YMCA on Huntington Avenue and later from Cullinane Hall on St. Botolph Street (built in 1911 and acquired by Northeastern in 1930.)

The older industrial character of what is today the campus south of Huntington Avenue provided the University with opportunities to gradually acquire older buildings built mostly in the first two decades of the 20th century. As a result, Northeastern has a modest legacy of older, re-purposed and renovated industrial buildings that add to the mixed stylistic, urban character of the campus.

Cullinane is still in service as an administration building and the Forsyth Building (built in 1926, acquired in 1949) serves as classrooms and student health services today. The largest collection of repurposed industrial buildings is the United Realty complex, formerly the United Drug Complex (built in phases between 1893 and 1913, acquired by Northeastern in 1961). This large brick and timber frame building fronting on Forsyth and Leon Streets serves a variety of academic and research uses. The complex also contains the University’s central steam plant within its core. The facility, along with Ryder Hall on the opposite side of Centennial Quad (built in 1913, acquired in 1976), presents significant challenges to serving contemporary academic uses, but does contribute to the West Village’s diversity of architectural character by providing some traditional industrial urban fabric along an important campus and city corridor.

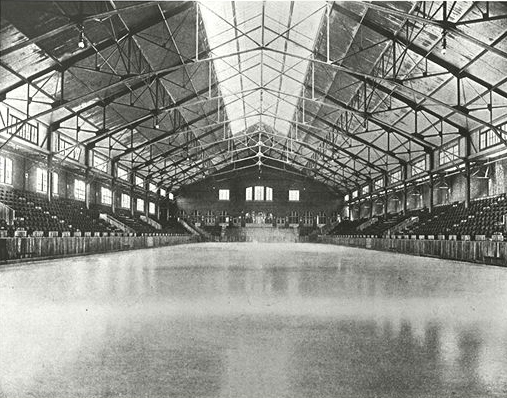

The Matthews Arena, formerly the Boston Arena, is another significant Northeastern building from the early 20th century, which serves as the University’s basketball, hockey and convocation facility. Matthews (built in 1906 and acquired by Northeastern in 1980) lacks any distinct architectural character on the exterior with the exception of a fragment of the ornate terra cotta entrance arch preserved on the building’s main entrance from St. Botolph Street. Despite the lack of notable exterior elements, the scale and intimacy of the interior space with its slender trusses and balcony seating, is a distinct reflection of its age and history as the world’s oldest indoor hockey rink.

Northeastern has also acquired and renovated a number of row houses and apartment buildings, built between the 1890’s and 1920’s, within the East Fenway neighborhood. The University values the traditional scale and fabric of these residential buildings and has served as a steward of the historic character of this important Boston neighborhood. In Roxbury, older residential and industrial fabric on the south side of Columbus Avenue, are also part of the inventory of older Northeastern facilities. The character of Columbus Avenue has been improved through NU’s renovation of these buildings from the 1920’s, augmented by the newer infill housing that has been built along Columbus in the past decade. The Fenway and Roxbury buildings contribute to the variety and richness of Northeastern’s urban campus context and identity. The master plan proposes to further enhance this character by improving the quality of the campus edges that abut these historic neighborhoods, and to enhance the public connections from the historic fabric through the campus.