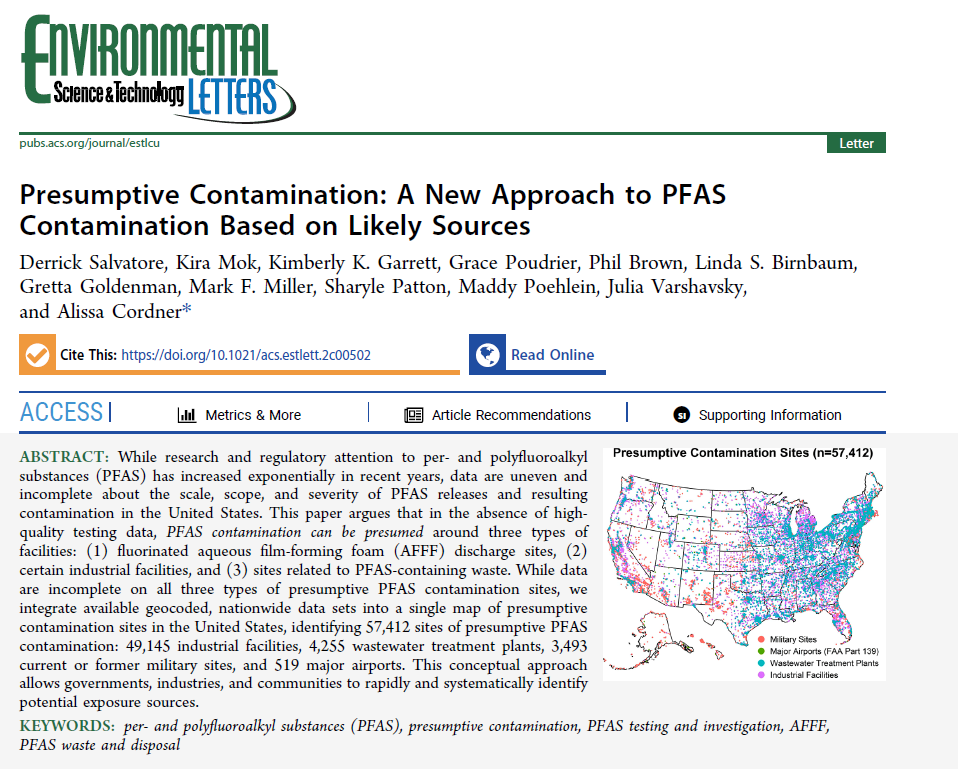

A new paper in Environmental Science & Technology Letters presents a model of “presumptive contamination” that identifies types of facilities that can be presumed to be contaminated with PFAS in the absence of access to testing. The paper’s co-authors include PFAS Project Lab co-directors Phil Brown and Alissa Cordner, current lab members Kira Mok, Kimberly Garrett, Grace Poudrier, and Julia Varshavsky, and former lab members Derrick Salvatore and Maddy Poehlein. The paper argues that “In the absence of high-quality testing data, PFAS contamination can be presumed around three types of facilities: (1) fluorinated aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) discharge sites, (2) certain industrial facilities, and (3) sites related to PFAS-containing waste.” Following this framework, the paper uses high-quality nationwide datasets to identify 57,412 sites of presumptive PFAS contamination in the United States. Despite the significance of such a large number, PFAS Project Lab co-director Dr. Phil Brown says that this is still “almost certainly a large underestimation” due to the “immense scope” of the contamination.

The sites identified by the presumptive contamination model were checked against 500 known contamination sites from our lab’s PFAS Contamination Site Tracker. 72% of the known sites were included in the model, showing that it effectively describes a clear majority of known PFAS contamination sites.

The model developed in this study provides governments, industries, and communities with the necessary information for the targeted, effective use of the limited available resources when it comes to PFAS cleanup and remediation. Dr. Kimberly Garrett, a post-doctoral researcher with the PFAS Project Lab, noted that PFAS testing is “expensive and resource intensive,” and the study “can help identify and prioritize locations for monitoring, regulation, and remediation.” This method allows state governments to identify likely sources of exposure and “turn off the tap” of PFAS contamination, providing an opportunity for prevention in addition to remediation.