Innovation, Labour, and Education

If the experts have it right, it’s time that we become more deliberate and thoughtful about career planning. We are living through the early stages of a technology-induced transformation of the labour market. The changes will be fast and severe. Those who can invest the time to understand the factors driving these changes will be well-positioned to navigate them. Universities can play a major role in this regard, as they have in previous periods of social and technological upheaval.

Concerns about technology wrecking havoc on our jobs are not new. Changes in technology can overhaul the labour market in short order. For example, at the start of the 20th century, agricultural labour constituted 40% of the workforce. Advances in crop production, storage, and transportation reduced this share of the workforce to 1.9% by the end of the century. Technology can also impact compensation. According to a Boston Consulting Group study, a welder can earn $25 per hour. But robots are increasingly used as replacements for welders at the cost of $8 per hour – a per unit cost that will undoubtedly continue to decline.

The conventional view, informed by history, is that the disruptive effects of technolological innovation are outweighed by its long-term benefits. Despite growing use of technology in occupations, real wages have risen over the last two centuries and quality of life standards have also dramatically increased. Between 1875 and 1975, for example, real wages increased three-fold in Britain, unemployment rates remained constant and life spans increased significantly.

Why This Time Might Be Different for Labour

Quote: “Software is eating the world”. Marc Andreessen. Wired Magazine.

Experts predict that the current phase of technological innovation may have more significant and long-term effects on labour than earlier periods of innovation. During the previous two centuries, technologies were used primarily to replicate and augment the physical labour of humans beings. The use of tractors in farming is an example of this way of employing technology. More recent technologies, however, are capable of replicating both physical and intellectual labour. Software programs, for example, can carry out increasingly complex tasks once performed by university-educated professionals—doing so more accurately and more quickly than humans, and without, of course, needing to rest periodically. The expectation is that artificial intelligence (AI) will escalate this trend. The potential of this technology has already been demonstrated by search engines, voice-activated personal assistants like Siri, and in the field of radiology.

The algorithms driving AI make digital technology advance more quickly as well. The technology can be disseminated across borders quickly, and can be combined and recombined easily with other systems. This flexibility further extends the impact of this technology.

Possibly the most ominous assessement comes from Larry Summers, former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. Summers states that capital “… can now effectively substitute for labour.” In other words, it is increasingly possible for those with the means to invest primarily in technologies that are less dependent on human labour.

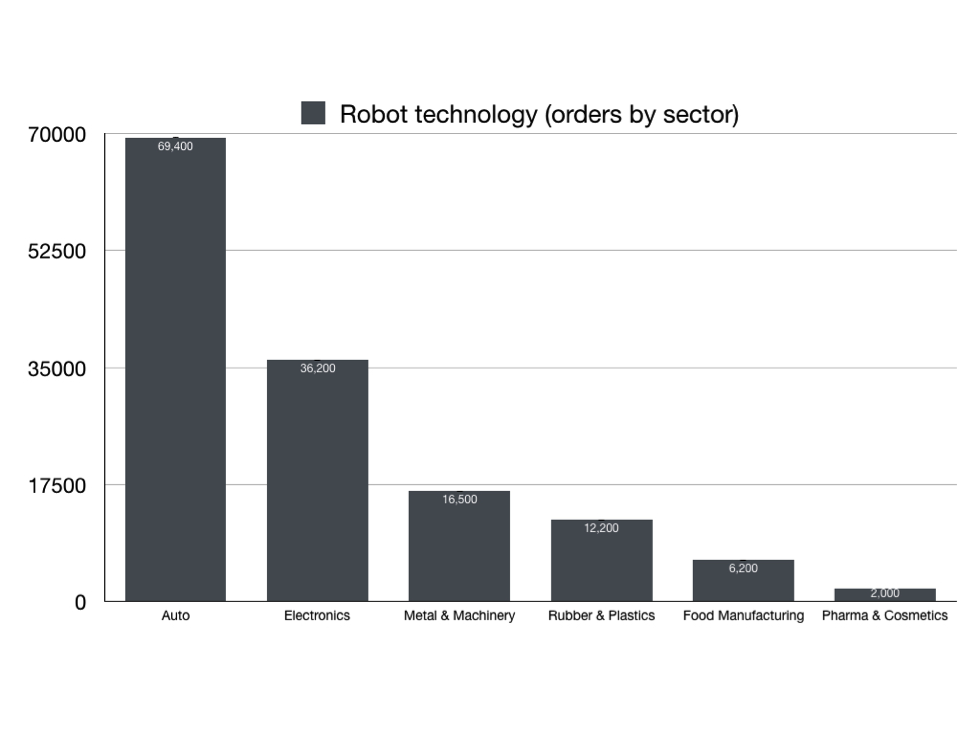

Figure 1. Use of robot technology (orders by sector)

Source: International Federation of Robotics, 2015. https://ifr.org/free-downloads/

It is important to note that the scale of technological transformation is far from uniform across all sectors. For example, the use of robots is higher in the automotive sector than in the pharmaceutical sector. There are significant variations within industries, as well. Jobs that involve a standard and predictable set of activities are relatively easy to codify and automate.

Less vulnerable are those jobs that consist mostly of non-routine activities. But the best opportunities are in a third category: those that are both non-routine and involve complex reasoning. Occupations that require considerable creativity, interpersonal social skills, complex decision-making, and the capacity to analyse abstract problems are difficult to outsource to technology.

Why and How Education Should Change

The heightened importance of education is evident in this context. Formal higher education remains the single most effective way for individuals to develop the knowledge and skills currently in demand. In 2017, these skills include AI programming and data analysis. But it is not simply students who are called upon to adapt to a changing landscape. This moment also challenges universties and colleges to think and act in new ways.

In his recent book, Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, Joseph E. Aoun (President of Northeastern University) argues that the emerging era demands new literacies – technological literacy, data literacy and human literacy – as well as skills that AI cannot easily replicate. These skills include critical thinking, entrepreneurship, systems thinking, and cultural agility. Coupling this educational framework with experiential learning opportunties is key to providing students with the skills to succeed in this new era.

Critically, education is no longer a “one-and-done” matter. The pace of change rewards those individuals and organisations that are continually learning new skills as conditions change. Traditionally, our educational system has relied on the credential to prepare students to succeed in the economy. The new educational model is focussed less on credentials and more on competencies. The workplace now demands a wide variety of educational tools that go far beyond our traditional credentialing structure. Modularized learning, stackable certificates, micro-badging, and industry-based learning are but a few of the emerging structures that seek to provide the public with lifelong, on-demand educational options. Northeastern University recently partnered with IBM to incorporate the company’s badging structures into Northeastern’s degree programs. This is the beginning of the kind of relationship that will define the education of tomorrow.

Technological innovation is not the only factor that is shaping the labour market. Other factors include globalisation, demographic changes (e.g. ageing workforce), immigration patterns, changes to trade policy (e.g. growing protectionism) and more. But technology is today’s wildcard—the single factor with the potential to impact where we work, how we work, the stability of our work lives, and our standards of living. Taking the time to understand how technology is giving shape to a new labour market will pay significant dividends.